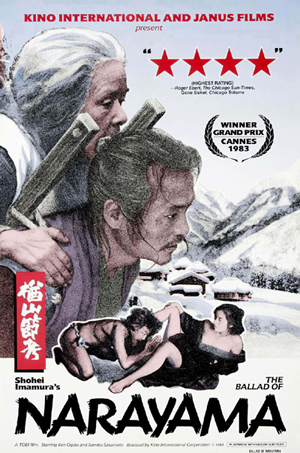

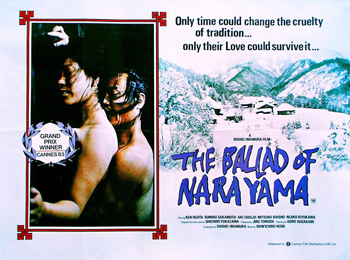

In 1956 Japanese author Shichirou Fukusawa published his first novel Narayama Bushiko or “The Ballad of Narayama” as it would become to be known internationally. The release proved highly successful for Fukusawa as Narayama quickly rose to the top of the best sellers list while reaping the benefits of critical acclaim.  It wasn’t long after in 1958 where The Ballad of Narayama found its first adaptation onto the big screen by way of director Keisuke Kinoshita, 25 years later it would once again meet celluloid under the direction of Shohei Imamura who would blend the established Narayama narrative with another Fukusawa's works “Tohoku no Zunmu-tachi” (The “Non-Heir” Son in the Family of Tohoku).

It wasn’t long after in 1958 where The Ballad of Narayama found its first adaptation onto the big screen by way of director Keisuke Kinoshita, 25 years later it would once again meet celluloid under the direction of Shohei Imamura who would blend the established Narayama narrative with another Fukusawa's works “Tohoku no Zunmu-tachi” (The “Non-Heir” Son in the Family of Tohoku).

Shohei Imamura renowned as a “pioneer of Japan’s New Wave movement” was already well known for showcasing bleak tales of Japan’s gritty lower classes and the dredging of society. Only four years prior to his release of The Ballad of Narayama Imamura had worked with the film’s formidable leading man Ken Ogata in the visceral and highly disturbing Vengeance is Mine, which told the true story of Japanese serial killer Akira Nishiguchi.

Imamura’s Ballad of Narayama begins with a slow pan across a desolate view of the snow covered mountains of Narayama, lingering about leisurely until fixating on remote village set in 19th century Japan. Here we are introduced to Orin (Sumiko Sakamoto), an elderly woman heading into her 70th year. Much to her chagrin, one wouldn’t know it from the tenacity and determination of her unseeming youthful vigor.

Since Orin’s husband had shamed and then left the family many years ago, from the age of 15 Orin’s eldest son Tatsuhei (Ken Ogata) has had to carry on as Totsan (leader of the house), while her other son Risuke (Tonpei Hidari) was forced to remain a lowly Yakko (2nd, 3rd or even younger son of the family). As a result he is left unable to marry with his meager existence dedicated to the labors of his families’ livelihood; in addition he emits a foul stench which has subsequntly ostracized him from the community leaving Risuke constantly bombarded by ridicule and disgust.

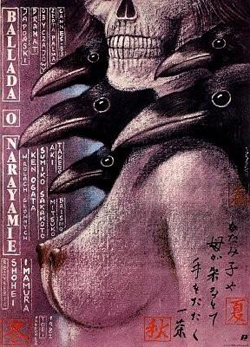

Tatsuhei, a widower of 10 months has several children of his own. The eldest of which being Kesakichi (Seiji Kurasaki), who himself gets quickly tangled with a local female from the village named Matsu. This leads to her becoming pregnant, and adds yet another mouth to feed to the already over crowded and food scarce homestead. It’s shortly before this when Tatsuhei is sent a second wife from a nearby village by the name of Tamayan (Aki Takejo). This pleases Orin greatly, who at her advanced age is well looking forward to her trip “up the mountain” to see the Narayama god. You see as a result of a widespread lack of food throughout the entire village, the elderly are given the “honor” of making a pilgrimage up to the peak of the near by Narayama mountains. Carried on the back of their eldest son, the elderly are brought to Narayama summit and left to die alone amongst the skeletal remnents of their long since passed kinsmen. Those who reach Orin’s age without making such a journey, are looked down upon and seen as a blight upon the community as they consume the badly needed resources intended for younger and expectantly more productive members of the community.

Tatsuhei is forced to struggle against the idea of carrying his mother to her inevitable demise, or his refusal of which would bring down the same great shame on his family for which his own father had done when he refused to bring his own mother up the mountain to meet the Narayama god.

The Ballad of Narayama is about as brutally honest as it gets. It exposes the harsh realities of survival under the threat of famine, and the many barbaric hardships which coincide with it. Here it's no longer about the individual but the continuation of the family, or more so the community. Female children are seen as a valuable commodity and often bartered away for salt, while their male equivalents are seen more as a burden and are regularly found laying dead and rotting shortly after birth whether it be a neighboring rice patty or a shallow unmarked grave.

It’s shocking to find such a strong woman as Orin determined to travel to her death to save her family from shame or future hindrance, regardless of her continued health and many contributions to the household. She simply cannot bear the dishonor to be or moreover for her family to be looked down upon by their community, going so far as to bash out her own front teeth to alleviate the towns scorn of her near full set and to appear to her family as if she’s ailing and ready to die.

If this is what the townsfolk do to their “loved ones”, it’s no wonder that they bear no sympathy for those they condemn for wrongs against the community. In retribution for thievery, the township drags off a guilty family to woods to be buried alive. Those who fight against it, are battered back into the hole with heavy wooden sticks. Even their daughter Matsu, who had since became impregnated by young Kesakichi and initiated into Oren’s family is fooled by her new grandmother in-law and thrown in along with them, the village showing zero tolerance or mercy for her unforgiveable alignments with the offending family. Understandably Kesakichi is at first severely saddened and angered by the loss of Matsu and his unborn child, yet disturbingly relatively shortly after she is but a distant memory as his interests soon attach to another local girl.

Sex also plays central role throughout the community. Viable woman are short of supply, as their often sold off at a young age to neighboring villages or quickly married away. As such the sexed starved Yakko are forced to go unwed and unfulfilled, some of whom go so far as to have sex with the local bitch IE the neighborhood dog if secret forniction proves unsuccessful otherwise. Of greater impact is the rampant birthrate, bringing with it many more potential mouths to feed and the inevitable aforementioned unfortunate deaths and barters.

Imamura’s direction here is superb, a shinning example being his continued insistence of humanity’s primal nature through various intercut sequences from that of insectile copulation or their more carnivorous feastings in relation to the current narrative. It works wonderfully without it being overpowering or appearing contrived.

The strength of The Ballad of Narayama unquestionably lays with its engrossing tale and unforgiving look into humanity at its most primitive depths. While for some it may prove too real and cruel a look into a frantic scramble for survival, it offers a candid view rarely shown in so raw a light and one well worth looking into if only for but a horrified glance into what could be.

The Ballad of Narayama has recently been released by AnimEigo in region 1 format, and is presented in it’s original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Their release is anamorphic, coming complete with on screen production notes, still gallery and trailers.